In 2013, after the Indonesian government renewed its push to halt the export of raw minerals and several million miners lost their jobs, I began to see huge growth in the local lapidary industry. It seemed every villager across the archipelago had become a rock hound! In West Java, every machine shop was making rock saws and Genie style grinding machines. An explosion of “Mata Cin Cin” cabochons from a rainbow of colored agates and jaspers were pouring into the local markets.

A new publication called “Indonesia Gemstone” went into print in mid 2013. Tales of new diggings and their locations complete with maps, helped buyers find their way to new finds. Everybody became an expert cab cutter. Local government and entrepreneurs in the provinces stepped in to promote the handicrafts and sponsor them in trade shows and exhibitions.

I first saw the “Batu Manakarra” in Sukabumi at a friend’s garage. One kid was holding the orbicular agate cluster, while another pounded it with the pressure washer they usually washed the car with. Small orbs and wads of blue-green clay spattered into the gutter.

As I usually kept an eye out for lapidary material, I dismissed this rather quickly thinking the friable material would certainly fall apart on the rock saw. I suggested if they collected the loose orbs, I could find a use for them.

Within a couple of months, the Manakarra was arriving in West Java warehouses by the truckload. I rounded up a few specimens to test cut. The result was as expected, not a solid material. 95% of what I saw on offer to Chinese and Indian buyers was far from attractive. Mostly dull surface, gray, brown and beat up. Some contained patches of purple, lavender and green but when dry, were still dull and not collector quality stone.

I sent a few samples to Mark Lasater in Tucson in late 2015. He is a creative genius when it comes to difficult materials. By February 2016, he was testing public response with finished product in his booth at the AGTA show (American Gem Trade Association).

This resulted in a deluge of requests and I struck out on a scavenger hunt thru the tons of the material arriving weekly from the field. In no time, I realized I needed to put a team in play at the mine site to secure the better stones as brokers in West Java had begun taking bids on crates of Manakarra sight unseen.

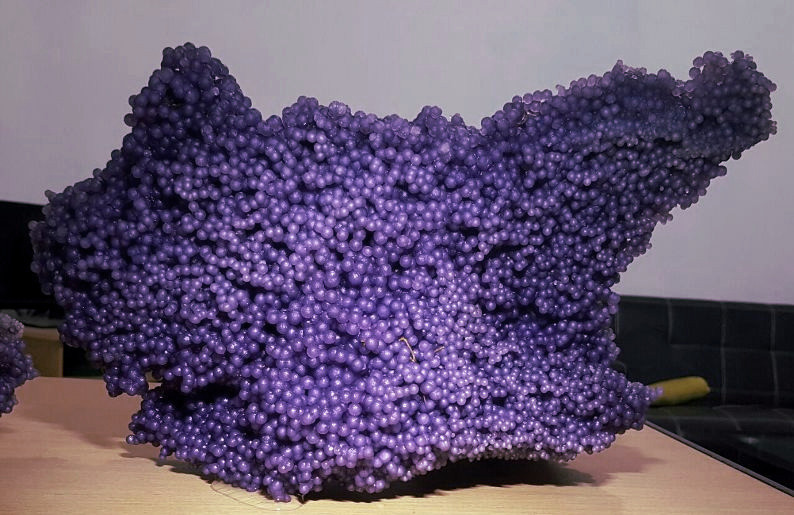

Another cutter in the US took samples and worked out how to polish the orb clusters. He called it “Grape Agate” and in fact the Manakarra often looks like a cluster of grapes.

I began to notice an evolution in the quality the team was sending me. Specimens of rich uniform color were being mined. The quality pieces were bright, glittery and vibrant in color. I decided to document the difference and map out the geological setting, so plotted a course to east Indonesia in October 2016.

On arrival, my West Java team met me at the airport. Within 30 minutes we were visiting local stone brokers and I was taking notes. The stone was already so popular that restaurant owner’s, government officials, even school teachers were moonlighting as stone brokers. It seemed everybody with a laptop or a smart phone was in business on Facebook selling Batu Manakarra.

Miners came from dozens of villages, even some many hours away from the diggings. Mostly young guys, yet even some over 70 years old were trenching into the steep hillsides. Some northern digging fields were on agricultural lands and others to the south were in the forest.

The tale of discovery leads to a beach far from town. Apparently locals noticed the round agate orbs in the sands and more massive agate wads in the gravels near the mouth of a river draining the rugged coastal mountains. There was a brief digging frenzy along the coast which rapidly let to the river where explorers found their way upstream to the primary deposits with less erosion damage, larger pieces and better colors.

The word for beach in Indonesian is “Pantai”. It suddenly dawned on me that “Batu Manakarra” is named after the famous “Manakarra beach”. Clearly an attempt by some stone dealer to lead the competition astray! Unfortunately, with the advent of the Internet and Facebook, secrets don’t last long anymore but the name stuck.

There is one feature that will deter the average rock hound, the mining area is located in a pronounced wedge of land which juts westward from the shoreline like the tail of a whale. The terrain consists of rugged mountains over 500m high and deeply incised valleys. The digging fields are scattered in the steepest most central part of this region. It is a knee busting adventure to reach the portals. It is either blistering hot or pounding rain!

According to the provincial department of mines and energy (ESDM), this entire mountain range consists of a Miocene age volcanic unit dominated by mafic lavas, volcanic breccias and tuffs. I met with the director and later with his geological team. They glossed over the agate discovery as if it would be gone tomorrow. Of greatest concern was mine safety, about which there was a meeting of departments scheduled the following week including police, forestry and the army.

In the morning, I visited the discovery beach with a local guide and ex miner. His in-laws live right off the beach. He described how they first dug the Manakarra on the beach and then followed it up the river to just past the 4th row of hills. Eventually, they began recovering better color pieces from the hillsides. In late 2014, villagers from other nearby villages began prospecting their streams and finding Manakarra. Using steel rods they probed the soils and followed the hard agate up onto the slopes.

At the northern end of the Manakarra mining district, just off a muddy road, we saw an 11m deep pit and trenches cut into hard rock in a Cacao plantation. The rocks were porphyritic pillow lava’s and volcanic breccias of the same composition.

Two and a half km further south, open pits and short adits were carved into the steep slopes both sides of the river. The streams were choked with tailings. This was the same river that I visited on the beach 10km to the south. I hiked into the digging fields with a local miner. We took a short cut down from the ridge top trail but were cliffed out 30 meters from the stream. As we hacked and chopped our way across the steep slope, we stumbled into a hornet’s nest and both dove thru the brush and tumbled into the creek below.

Rocks we encountered were all similar to digging areas in the north. A 525m peak divided the 2 mining areas. After the hornets tagged me and the tumble down the mountainside, I lost my momentum for the day and retreated back to the trail bikes. It was the tallest point in the Manakarra mining district. I do not know what lies up that peak, but reports are that no Manakarra is found there.

After a day’s break, we returned to the field. The richest color and most glittery druse coated specimens were reported from southern part of the mining district.

We stopped along the paved road to pick up a local miner as an extra hand. Several soldiers were there rounding up volunteers to search for a lost miner. Our guy had already been sent ahead. The soldiers checked my passport and quizzed me on my intentions before getting on with their mission. They were surprised to see a foreigner in the area. I assured them after 28 years in country as a field geologist, there was nothing new to me.

We headed down a mud track as far as the trail bikes could go, then, hiked down the steep trail to the river below. Heavy rains the previous day had swept over the gravel terraces 2m above the current river level, laying down the grasses and small shrubs. We walked downstream to a shallow stretch and waded across the fast moving waist deep river before heading up a tributary toward the mines. The trail quickly disappeared in the steep canyon and we followed the stream climbing over boulders the size of cars.

All the rock was the same as seen at previous mining areas, porphyritic lavas and breccias of same. Small grooves for footings had been cut into the boulders and canyon walls by the miners. We met a team of soldiers and about 50 miners coming down the stream poking sticks into the swirling pools and behind boulders in search of the miner who was swept away by the previous days flood. (Four days later his body was found 15km away along the coast.)

Another 2 hours up the stream, we met several miners coming down portering heavy loads of Manakarra. The rock was coated with a thick wad of blue-green clay and we could not get any idea of quality. They were in a hurry to reach the main river below before another rainstorm hit and trapped them on the wrong side. This also spooked my team. After 4 hours we reached the diggings. Narrow, un-timbered adits were spaced at 5m to 15m intervals across the slope for about 350 meters. There were several shafts and blue tarpaulins indicated additional workings up and across the slope. Not all were active, it was clear many were already abandoned.

The miners were digging along the chilled margins of pillow lavas. Large pillow shapes were evident in the cliff face and most of the borders of the pillows had pits from miners prospecting. Many miners had boarded up the entrances to their workings and joined the search teams down on the river. The remaining guys let me into their diggings and explained how they followed the blue-green clays as a lead to the pockets of Manakarra agate clusters. The host rock underground was again the ubiquitous porphyritic lavas seen at other mining sites. The depth of some adits exceeded 35 meters into the hillside. In the underground, the extraction sites were carefully infilled with rock debris to prevent collapse. The slope below was covered with tailings for several hundred meters. A collection of fresh sawn timbers suggests they intended to continue digging.

We made it out before dark and were lucky the dreaded rains never came.

In review of my adventure to thru the Batu Manakarra mining district, it appeared that all the easy winning stone from farmer’s fields and along the roads had been harvested. We passed many areas which the locals pointed out had experienced brief mining activity with little reward. Most of that early production had been weathered and worn and miners had come to recognize the value of unbroken stones with attractive colors.

In the new areas, small teams of 4 or 5 miners were working each hole but still many dry holes were dug. New hard rock production from these remote areas can be stunning but was hard won. Although the mining teams at each hole are said to operate independently, each team seems to report to a broker in town who sells their stone and shares the reward.

In the southern portion of the district, distinct glittery orb clusters and associated late sugary quartz crystals are found. I suspect this is more proximal to the volcanic center or up-flow zone and the waning pulses of less silica saturated hydrothermal solutions resulted in crystallization of druses and sugary quartz.

Recent mining activity seems most concentrated in this area probably as the mining becomes more difficult, the miners target higher value specimens.

My simple theory on the origins of orbicular Manakarra agate clusters is based on a typical hydrothermal event.

The dominant composition of the volcanics observed were potassium rich andesites as evidenced by abundant potassium feldspar pheonocrysts, biotite and low quartz. I would classify the material as a Trachy-Andesite porphyry.

The porphyritic Trachy-Andesite lava erupts into cold sea water. The lava forms tubular and pillow shapes; it is more viscous than a basaltic lava, therefore eruption is a somewhat more phreatic event and there are lots of breccias. The margins of the pillows and a lot of breccia fragments are chilled, incomplete crystallization occurs and creating a volcanic glass.

The chilled pillow margins and breccias are weak points and hydrothermal solutions penetrate the volcanic pile thru the chilled margin corridors. Hydrothermal solutions leach the silica from the volcanic glass becoming silica saturated increasing the pH and further decomposing mafic minerals in the lava producing illite or smectite clay (high Ca & Mg).

The decomposition and deposition of chalcedonic silica is episodic and subject to solution saturation levels in silica. Miners always find the Manakarra orb clusters hosted in the blue-green clay but the clusters are limited to small pockets. Often we find a flat base of chalcedony and it seems the orbs rain down and loosely adhere to one another. Other times we find single floaters on a bed of clay.

I thought the orbs must have formed on some sort of nucleus but proof of that is not yet evident.

A crossed polar micrograph of a Manakarra thin section cut by Terry Moxon, exhibited a Maltese Cross. According to Terry, this uncommon phenomenon results from twisting of the quartz C-axis during rapid growth of a fibrous chalcedony. This is in contrast to the layered growths of chalcedony which forms by deposition in concentric layers in a void such as with agates.

The chemical analysis and XRD indicate composition of the Manakarra is dominantly chalcedonic quartz (SiO2) with very minor potassium, aluminum, calcium and magnesium which are likely decay products of the original volcanic host rock. The blue-green illite or smectite clay is also typical of the decomposition of a mafic host. In this case, aside from SiO2, only minor Ca/Mg/K/Na/Al was detected (<1%).

The weight percent of trace elements is so low that I cannot comment on which are likely contributors to the rich colors we see in the Manakarra specimens recovered from insitu volcanic host rocks.

|  |

Needless to say, there is a great demand and appreciation of this colorful material both by jewelers and collectors. This pendant by Lexi Erikson made the cover of Lapidary Journal’s November 2016 issue.

These polished grapes were done by Joe Jelks at Horizon Mineral.